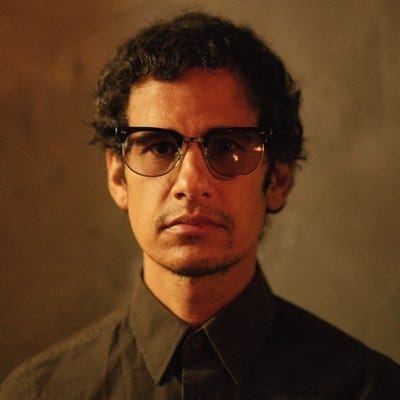

6 lessons from analysing the life and music of Omar Rodriguez-Lopez

You don't need to be a budding guitar hero to take inspiration from his approach

Anyone who knows me personally will be aware that I have an unhealthy obsession with musician Omar Rodriguez-Lopez. Perhaps the origins of this man crush were the age and stage I was when I first discovered his music, or maybe it was down to him being, like me, a left-handed guitar player, and I therefore viewed him as some kind of kindred spirit. More likely is that his wild stage antics had an influence, always performing with trademark abandon.

All these factors no doubt played their part in getting me hooked on his artistic output, though I suspect the primary reason was this: he’s indisputably an innovator, playing and writing in a completely unique style, and is one of the finest musicians of his generation.

For this reason, I thought it useful to examine his artistic idiosyncrasies in an attempt to identify, at least partially, what makes him so special. And so with that preamble, below are 6 insights I’ve gleaned from examining his career, which will hopefully be of use to both musicians and non-musicians alike.

6 lessons from analysing the life and music of Omar Rodriguez-Lopez

Lesson #1: Work ethic

While ‘worth ethic’ may feel like a trite observation, Rodriguez-Lopez seems to operate with a level of tenacity not often seen. Long-term creative partner Cedric Bixler-Zavala attested to ORL’s deep commitment to touring in the earlier phases of his career, and revered drummer and former bandmate Jon Theodore has stated:

‘I’d never met anybody that worked as hard. From morning to night, completely obsessed’.

Theodore’s comments feel especially salient, acting as a reminder of how driven and focused one must be in realising any personal, professional, and/or creative goal.

Lesson #2: High creative output

As well as his work in bands like At the Drive-In, De Facto, The Mars Volta, and Bosnian Rainbows, Rodriguez-Lopez has released 49 solo albums, is a prolific filmmaker and photographer, and has collaborated with numerous artists, including composer Hans Zimmer and Red Hot Chili Peppers’ guitarist John Frusciante. This may sound like a recipe for burnout for us mere mortals, but while quantity and quality are often presented as dichotomous, in reality they’re more friends than foes, with high creative output being crucial to creating high-quality work. Another vital lesson.

Lesson #3: Single-mindedness

Endorsing single-mindedness and presenting it as a valuable ‘lesson’ could reasonably be seen as ill-advised, as it’s a trait that is very much a double-edged sword, with the potential to encourage selfish and even reckless behaviour. Still, in the arts at least, design by committee doesn’t always work, and there are moments when one must be musically fascistic in order to achieve the highest aesthetic standards. In a recent interview, Rodriguez-Lopez said that part of The Mars Volta’s origins lay in growing tired of having to justify and explain artistic decisions, and being told ‘no’ too often.1

Lesson #4: Extensive cultural diet

In discussing his unique approach to music, Rodriguez-Lopez puts this down to soaking up a multitude of influences:

‘I’m just fond of music in general. Salsa, dub, and dancehall are all huge influences, along with country, folk, pop music, and electronic music like Richard James [Aphex Twin] or Roni Size. I love every form of music.’

This again feels pertinent for both creatives and non-creatives, as regardless of the sector we may be operating in, attributes like originality and creativity are attained through being zealous in feeding diverse, high-quality input into our minds. For what it’s worth, The Mars Volta’s Take the Veil Cerpin Taxt, specifically the riff between 3.40 and 4.36, is in my view one of the best examples of ORL’s innovative approach to creative amalgamation:

Lesson #5: Curiosity and lifelong learning

There seems to be an insatiable curiosity and desire for continual learning in Rodriguez-Lopez, and even now he believes he’s still ‘in training’. When talking about the cultivation of his music production skills, his eagerness to learn is palpable:

‘The root of my training was from Alex Newport, who came before Ross [Robinson]. Then Ross and then Mario [Caldato Jr.], because De Facto—the other band Cedric and I had—recorded with Mario C right around the same time. Then of course, there was Rick Rubin. My schooling was watching those guys and seeing what pieces of gear they had and asking questions about why they’d choose to use that particular gear.’

Lesson #6: Authenticity of artistic purpose

Finally, when examining Rodriguez-Lopez’s career, there is a deep sense that he would never compromise his artistic vision, and there is an emotional sincerity in everything he does. Philosopher of aesthetics Denis Dutton refers to this as authenticity of artistic purpose - a sense that the artist means it.

This attribute was perhaps most evident during At the Drive-In’s initial breakup in 2001, where despite being at the height of the band’s success, Rodriguez-Lopez and bandmate Cedric Bixler-Zavala opted to walk away from the group, citing artistic limitation as the reason. ORL later said that if the band had stayed together and persevered, he’d have been doing it for the wrong reasons:

‘I don’t think that expression or art should come second to anything else. I think the only reason to play music is expression - getting out the thing you have inside that can’t be conveyed through any language. I think when something isn’t real, people will perceive it.’

Concluding remarks

I feel these 6 lessons hold value for us, irrespective of whether we aspire to become music superstars or not. And while it’s understood, of course, that mimicking aspects of a musician’s career trajectory or skillset never guarantees similar outcomes, I nonetheless strive to keep these insights in mind as a guide for my own personal and creative journey. I hope they’re helpful for you, too.

Oh, this is awesome. I haven't listened to At the Drive-In and The Mars Volta in a while--this makes me want to revisit. 49 solo albums? Jesus.

Another insightful piece Sandy.

I love the line where you say one must be musically fascistic in order to achieve the highest aesthetic standards. This feels like a dilemma most musicians in a group face. Balancing the direction they want the music to go versus other members in a band.

Do you feel like you have this tension in your band?